To laser scientists, the Kerr effect is as fundamental as the lens or the mirror in the laser cavity. The effect describes the nonlinear phenomenon that governs the propagation of intense light, the mechanism that allows us to slice time into femtoseconds and the principle behind the “optical transistors” of the future. Many of us use the term daily, scribbling x(3) into notebooks and modelling self-phase modulation in simulations. Yet, the name attached to this profound effect often remains just that – a name.

Who was the figure behind the physics however? On 17 December 2025, we mark the 201st birthday of the Reverend John Kerr. The son of a fishmonger, Kerr was far from the archetype of the celebrated academic in a grand institute. From these humble origins, his curiosity and desire to use his learning drove his ambition. As many great scientists in the past, he was first ordained as minister of religion before realising his vocation as a scientist. Researching and experimenting, it wasn’t until his middle age that he made his world-changing discovery in a converted wine cellar.

As we rely on his insights to drive the next generation of quantum computers and telecommunications, it is fitting to look back at the “physicist of the coal hole” who first demonstrated that light could be modified by electricity.

Key Highlights

- The pioneer: We celebrate the 201st birthday of the Reverend John Kerr, who discovered the electro-optic effect in 1875 while working in a humble cellar laboratory known as the “coal hole”

- The discovery: Kerr proved that electricity could alter the refractive index of glass, turning an isotropic material birefringent with a response proportional to the square of the electric field (E2).

- The evolution: Originally used for high-speed photography shutters (faster than 100ns), the phenomenon has evolved into the “Optical Kerr Effect,” where the laser light’s own electric field drives the interaction.

- The application: This nonlinearity is the engine of Kerr-Lens Mode-Locking (KLM), enabling the generation of femtosecond pulses for deep-tissue imaging and precision metrology.

The 1875 Discovery: Electrified Glass

In the Victorian era, the search for a link between electricity and light was a major scientific objective, one that had eluded even Michael Faraday. Then in 1875, working with limited resources, John Kerr succeeded. His experimental setup was a masterpiece of simplicity: he bored holes into a block of glass, inserted metal probes connected to an induction coil and passed polarised light through the glass perpendicular to the electric field.

When the coil was activated, the glass, typically optically isotropic, became birefringent, behaving essentially as a uniaxial crystal. The electric field had aligned the material’s properties, altering the speed of light passing through it. Kerr was able to establish that this induced birefringence (Δn) was proportional to the square of the electric field strength (E):

Δn = λ K E²

This quadratic relationship, now known as Kerr’s law, distinguished his discovery from linear electro-optic effects and implied that the phenomenon was universal, existing in all materials including liquids and amorphous solids.

The Bridge: From Shutters to Solitons

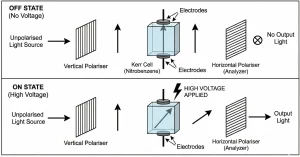

For nearly a century, the primary application of this discovery was the “Kerr Cell” – a vessel filled with a responsive liquid such as nitrobenzene situated between crossed polarisers. Acting as an electro-optic shutter, the cell could block or transmit light with a response time in the nanosecond range.

This capability revolutionised high-speed photography. While modern digital cameras generally struggle to exceed shutter speeds of 1/8000s (125,000ns), early Kerr cell shutters achieved speeds faster than 100ns. This allowed scientists to capture ballistic projectiles in flight and freeze rapid chemical reactions, providing the first glimpses into processes previously too fast for the human eye to register. However, relying on heavy high-voltage drivers and often toxic liquids, these devices were unwieldy and restricted entirely to the laboratory.

While the Kerr cell continued to serve in these specialised imaging roles, the invention of the laser in 1960 transformed the Kerr effect from a high-voltage modulator into an intrinsic feature of light-matter interaction. In this “Optical Kerr Effect” (OKE), the external voltage is replaced by the electric field of the laser beam itself. Unlike the nanosecond molecular reorientation in a Kerr cell, this electronic distortion is virtually instantaneous (in the order of femtoseconds), allowing the light to modify the refractive index of the medium it traverses described by the equation:

𝑛(𝐼) = 𝑛₀ + 𝑛₂𝐼

This simple equation demonstrates that a powerful laser beam does not merely travel through a medium; it dynamically alters the refractive index of the material as it propagates.

The Heartbeat of Modern Lasers: Kerr-Lens Mode-Locking

The most transformative application of this optical nonlinearity, and one which is a pillar of modern laser physics, is Kerr-Lens Mode-Locking (KLM). The KLM mechanism powers nearly all modern femtosecond lasers.

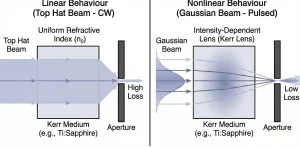

KLM exploits the spatial Kerr effect, a phenomenon known as self-focusing. A typical Gaussian profile laser beam is more intense in the centre than at the edges. This contrasts with a “Top Hat” profile, where intensity is uniform; without the intensity gradient of the Gaussian beam and with which the Kerr effect would simply retard the phase uniformly rather than creating a focusing lens.

As the Gaussian beam travels through a Kerr medium (such as a titanium-doped sapphire crystal), the higher intensity in the centre induces a higher refractive index than the wings. This creates a gradient that acts as a positive lens (effectively a “Kerr lens”) which focuses the beam.

Laser engineers exploit this by aligning the laser cavity to favour this focused state. A short pulse, which has high peak intensity, will trigger the Kerr lens and be focused tightly, passing through the system with minimal loss. By contrast, continuous-wave (CW) light has low intensity, does not trigger the Kerr lensing effect, and is blocked by an aperture or poor overlap with the pump beam.

These platforms have become significant tools in fields such as neuroscience, where they enable two-photon excitation microscopy to image deep into living tissue without damage; in attosecond science, where they help capture the motion of electrons; and in optical coherence tomography (OCT), where they drive the supercontinuum sources used for high-resolution medical imaging.

The Future: Microresonators and Quantum Gates

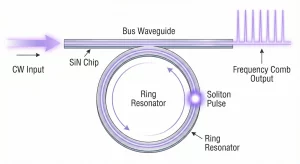

The legacy of John Kerr continues to unfold in the 21st century with the advent of Dissipative Kerr Solitons (DKS). By confining light within microresonators (microscopic rings made of Kerr-active materials such as silicon nitride) researchers can generate optical frequency combs on a chip.

In these microresonators, a simple continuous-wave pump laser drives the system. The Kerr nonlinearity compensates for group velocity dispersion, allowing stable packets of light (solitons) to circulate indefinitely without changing shape. This technology promises to shrink room-sized metrology equipment onto millimetre-scale chips, potentially replacing hundreds of individual lasers in telecommunications systems and enabling compact lidar systems for autonomous vehicles.

Furthermore, the Kerr effect is poised to enter the quantum realm. Theoretical mechanisms suggest that strong Kerr nonlinearities could enable single photons to interact with one another, facilitating the creation of quantum logic gates – the “Holy Grail” of optical quantum computing.

Conclusion

From a cellar in Victorian Glasgow to the silicon chips of the future, the work of John Kerr stands as a testament to the enduring power of fundamental physics. What began as an observation of birefringence in a block of glass has evolved into the engine driving the fastest events in science.

Whether it is slicing time into femtoseconds to watch molecules bond, or guiding autonomous vehicles via chip-based lidar, the quadratic nonlinearity discovered by the Reverend John Kerr remains a significant force shaping the light of the 21st century.

If you want to discuss the integration of nonlinear optics into your laser system designs, please get in touch.

FAQs

Q: What is the Kerr effect?

A: The Kerr effect is a nonlinear optical phenomenon where the refractive index of a material changes in response to an applied electric field. It was discovered by John Kerr in 1875, who showed that the change is proportional to the square of the electric field (𝐸²).

Q: How is the Kerr effect used in modern lasers?

A: In modern lasers, the effect is used for Kerr-Lens Mode-Locking (KLM). The intense centre of a laser beam increases the refractive index, creating a “lens” that focuses the beam. This allows the laser to selectively amplify high-intensity pulses, generating femtosecond bursts of light.

Q: What is the difference between the Kerr effect and the Pockels effect?

A: While the Pockels effect is linear, the Kerr effect is quadratic (proportional to the square of the field). This means the Kerr effect can occur in all materials, including liquids and amorphous solids like glass, whereas the Pockels effect requires crystalline asymmetry.

Q: Who was John Kerr?

A: John Kerr (1824–1907) was a Scottish physicist and ordained minister. He conducted his groundbreaking research in a converted wine cellar known as the “coal hole” at the University of Glasgow, demonstrating that light could be controlled by electricity.

Q: What are the future applications of the Kerr effect?

A: Future applications include Dissipative Kerr Solitons (DKS) for chip-based frequency combs in telecommunications and lidar , as well as potential quantum logic gates for optical quantum computing.